flowboard is lovable for animators. we hit 100k+ views, 100+ github stars, ~200 users, and 1k animations generated. instead of spending hours drawing frames from scratch, creators can now focus more on output rather than the tedious work.

it has been a while since i attended a hackathon (surviving 1a in uwaterloo). flowboard was inspired by vibedraw and this tweet, which we took the intersection of.

we refined the idea into a frame-by-frame video generation tool for animators. we had to pivot from long form video generation because veo is crazy expensive.

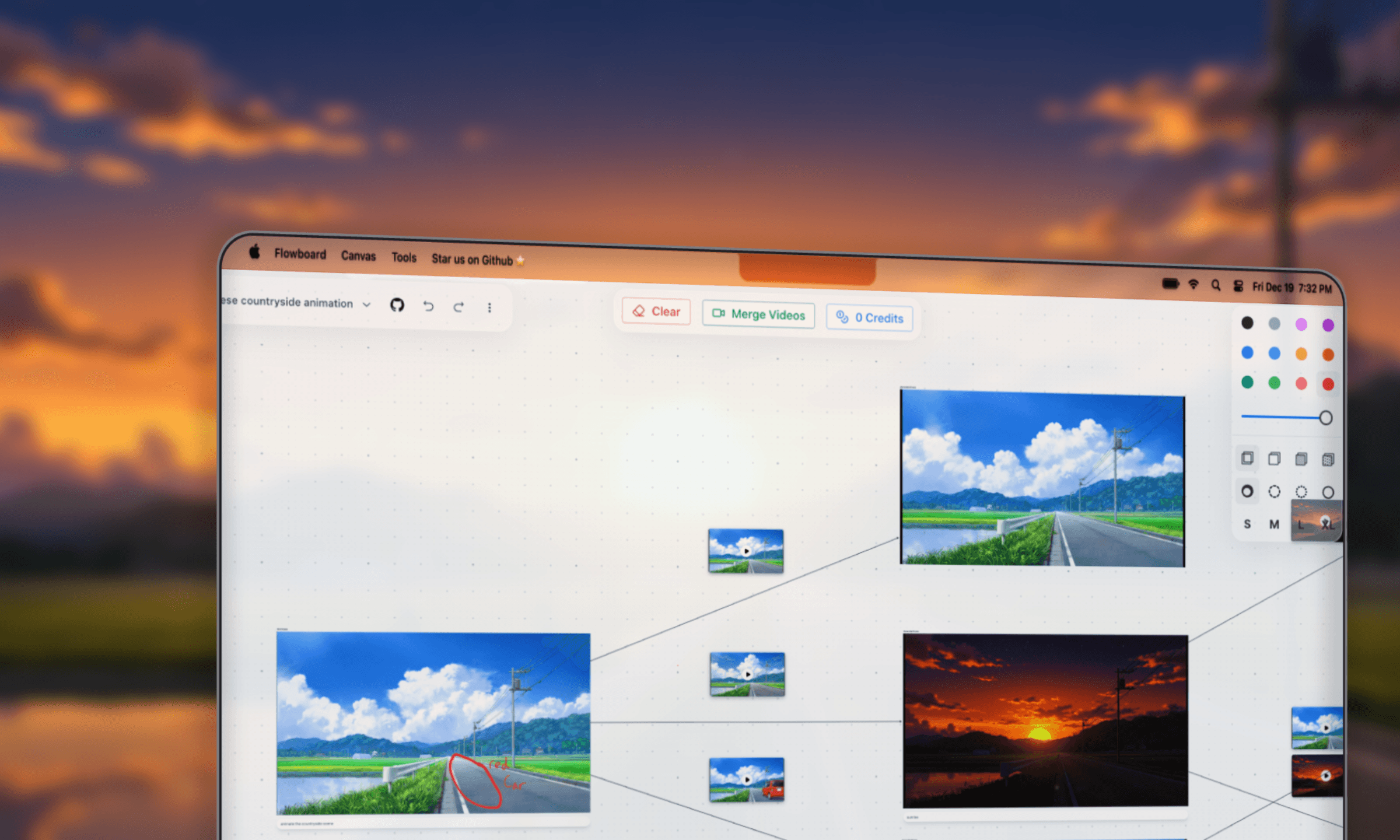

creating storyboard trees on the canvas

creating storyboard trees on the canvasin this way, we could generate one 5-8s clip at a time and then write global context to make clips relate to one another.

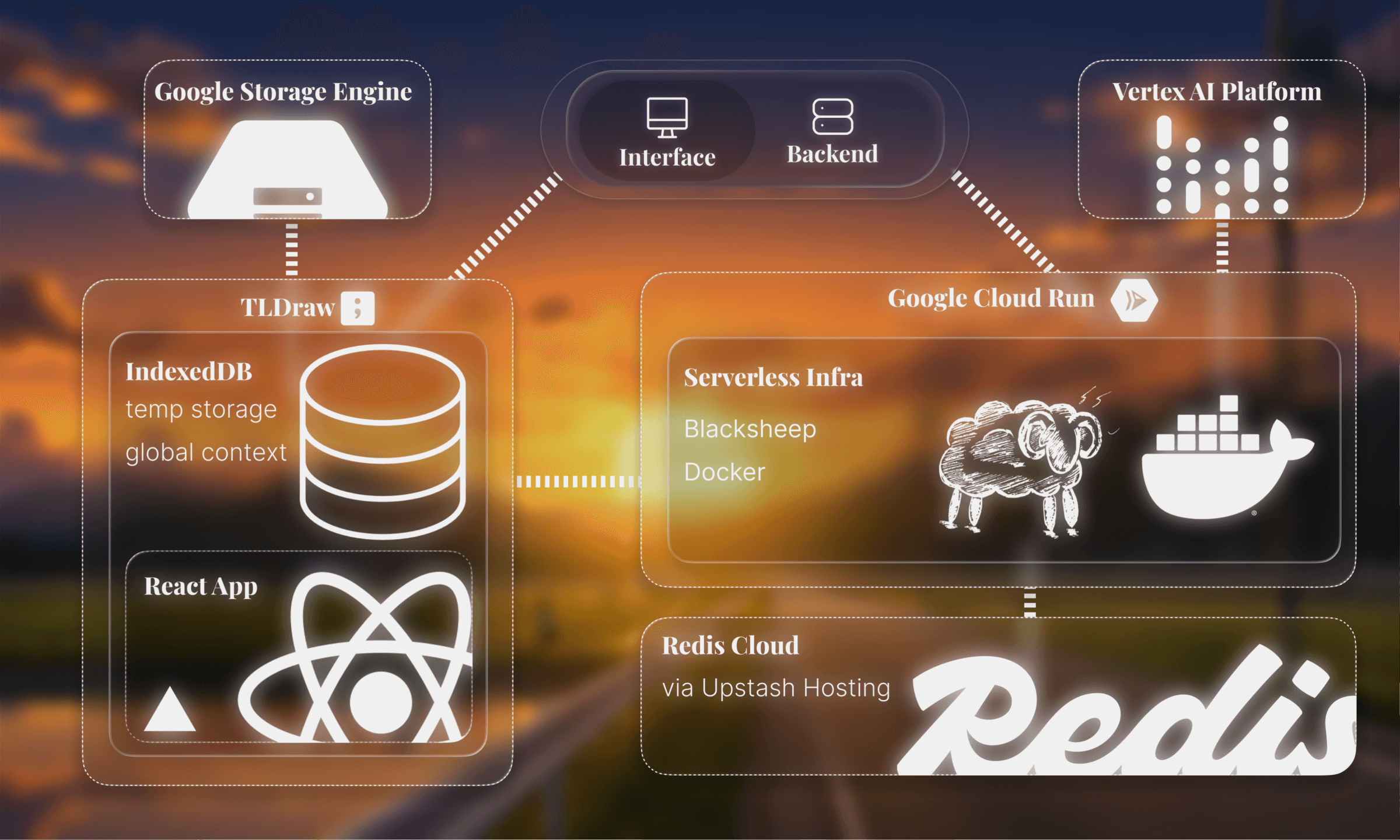

flowboard consists of python serverless infra, dockerized and hosted on gcp, and a react interface hosted on vercel.

client-side, flowboard uses the tldraw sdk for the canvas. and indexeddb as a low level client-side store for global context and temporary storage.

on the backend, google cloud run deploys and runs a dockerized blacksheep asgi service. redis is used for caching while vertex ai handles veo generation.

google cloud storage facilitates file storage via buckets.

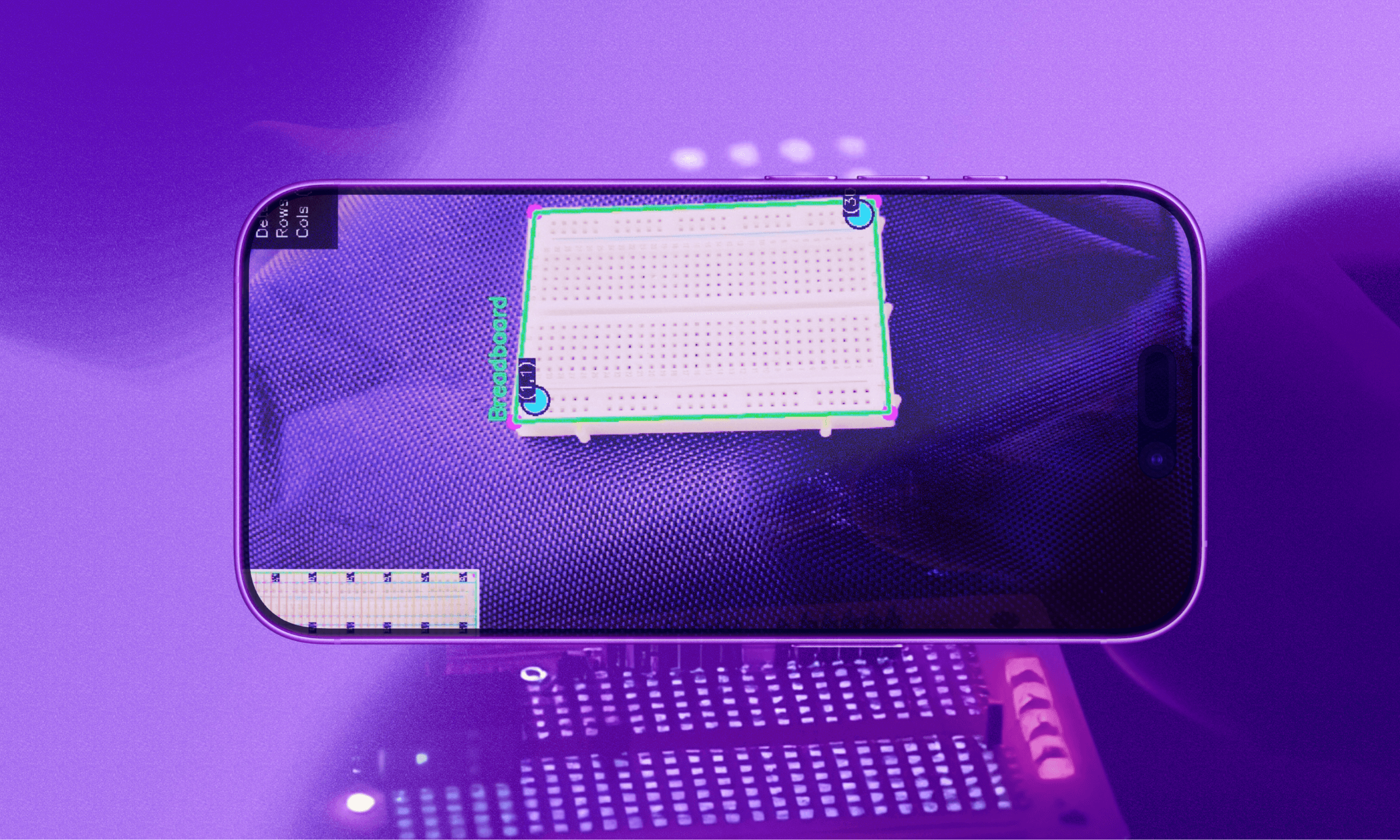

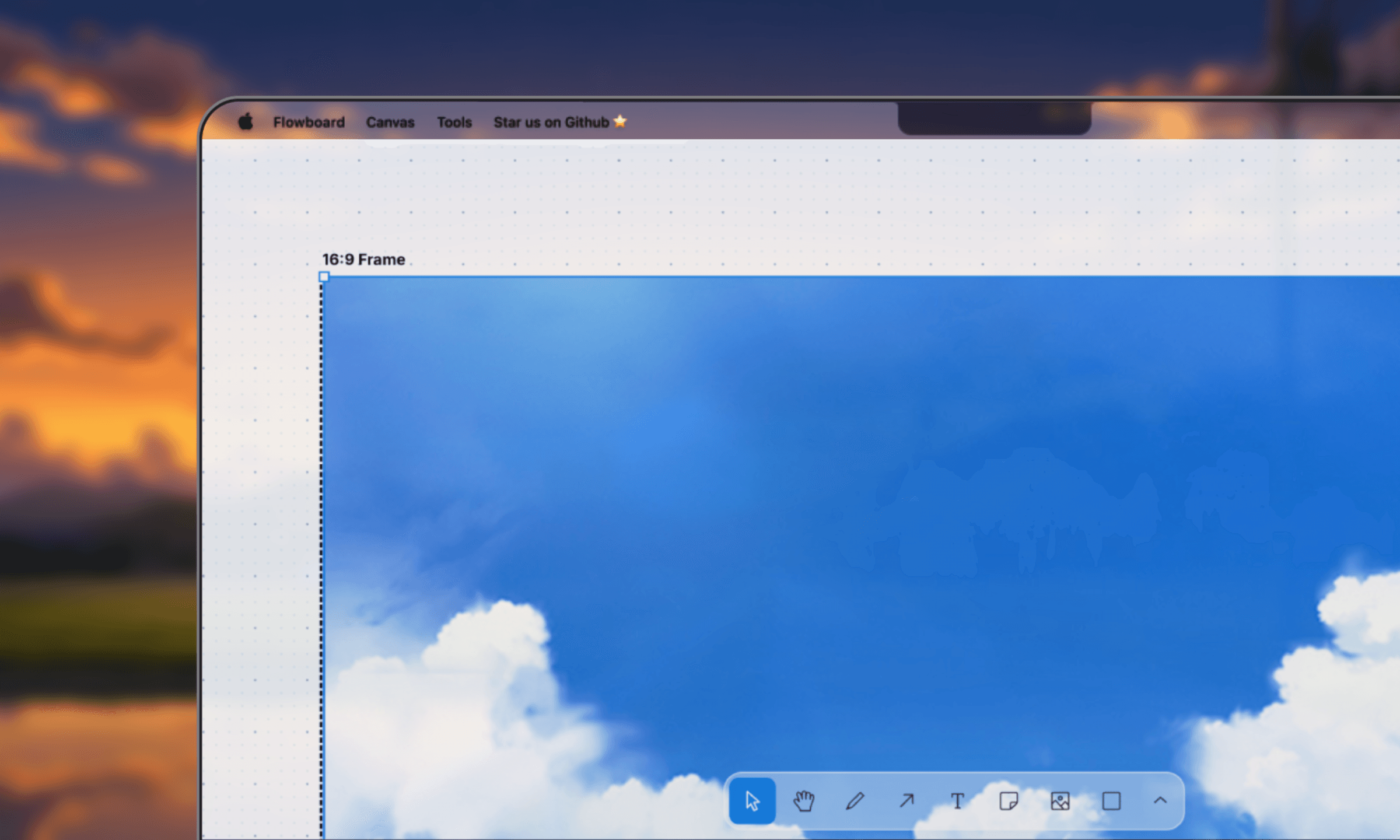

each flowboard project begins with one 16:9 frame. this is the starting frame where users can upload images and annotate with the built in tldraw tools, then generate animations.

on an infinite canvas, users can design full animation storyboards one frame at a time.

initial ui pitfallsalthough flowboard is basically a 'tldraw wrapper', there are many small nuances that made the initial development incredibly difficult.

the nature of this concept is genuinely more intricate than it seems. sure, parents have children, which have more and more children, like a directed graph.

but what if the user wants to change previous frames? and how could we get each sequential frames to be coherent when they are generated in seperate api calls?our first main issue was with bounds. tldraw shapes were not the nicest thing to work with, and we spent a long time getting the initial 16:9 frame to bind images and native user edits onto the frame.

to fix the bounds problem, we created a parent-child relationship.

frontend/src/components/canvas/FrameActionMenu.tsx// creates a child shape

const shape: TLShapePartial = {

id: imageShapeId,

type: "image",

x,

y,

parentId: frame.id, // this sets the parent

props: {

assetId,

w: scaledW,

h: scaledH,

},

};

// deleting all children for a parent

const childIds = editor.getSortedChildIdsForParent(shapeId);

if (childIds.length > 0) {

editor.deleteShapes(childIds);

}

the key idea was that: tldraw shapes needed explicit parent-child relationships via parentId rather than positioning shapes "inside" the frame's bounds.

child shapes use relative coordinates to their parent. when you place an image at (x, y) with parentId: frame.id, those coordinates are relative to the frame's top-left corner, not the canvas.

additionally, when frames move, children move with it automatically, and we get/delete all children with getSortedChildIdsForParent() without searching the entire canvas.

our second issue was positioning the arrows correctly.

our ui involves arrows, which indicate order of frames.

we initially tried to manually placed the arrows, but we eventually ran into critical issues: the ui would break when frames were moved around, and glitch when overlapping.

we fixed this with tldraw's binding system:

frontend/src/components/canvas/ArrowActionMenu.tsxconst info = useValue(

"arrow info",

() => {

const arrows = editor.getCurrentPageShapes().

filter((s) => s.type === "arrow");

return arrows.map((shape) => {

// Get tldraw's computed bounds (not manual calculation)

const bounds = editor.getShapePageBounds(shape.id);

// Position at arrow's center

const center = {

x: bounds.x + bounds.w / 2,

y: bounds.y + bounds.h / 2,

};

return { id: shape.id, x: center.x, y: center.y /* ... */ };

});

},

[editor]

);

instead of manually placing the arrow, we use editor.getShapePageBounds(shapeId) which returns tldraw's computed bounds for the arrow based on its bindings.

when frames move → bindings update arrows → bounds change → tldraw's useValue hook re-computes → ui repositions automatically.

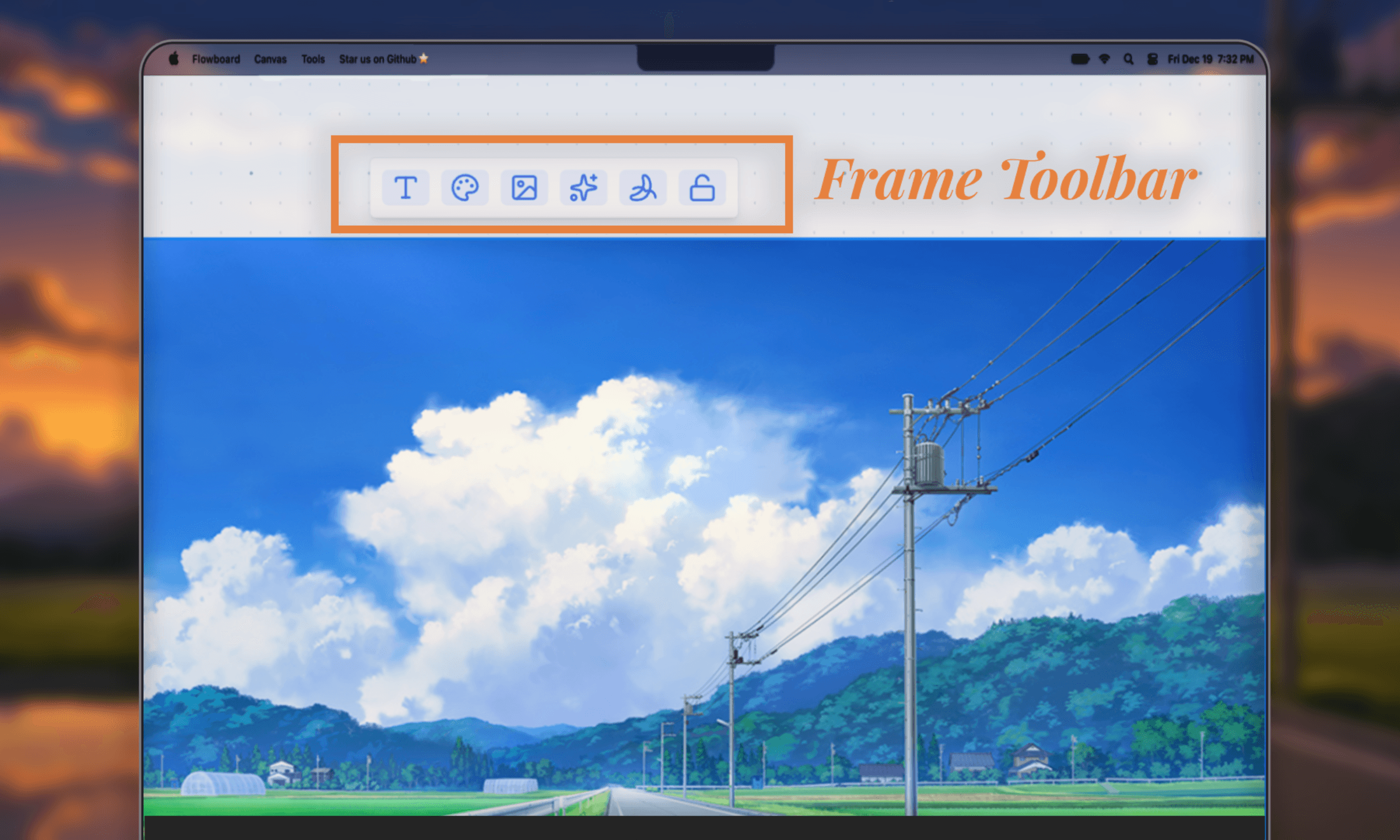

frame toolbarthese are additional action for the user on top of the tldraw native tooling.

the three most crucial tools include image upload, image enhancement, and generate video.

uploading an imageuploads an input file directly into the frame. it scales the image to fit within frame while maintaining the aspect ratio.

frontend/src/components/canvas/FrameActionMenu.tsxconst imageShapeId = createShapeId();

const shape: TLShapePartial = {

id: imageShapeId,

type: "image",

x,

y,

parentId: frame.id,

props: {

assetId,

w: scaledW,

h: scaledH,

},

};

editor.createShapes([shape]);

it then creates a shape and sets parentId: frame.id, like described in initial ui pitfalls.

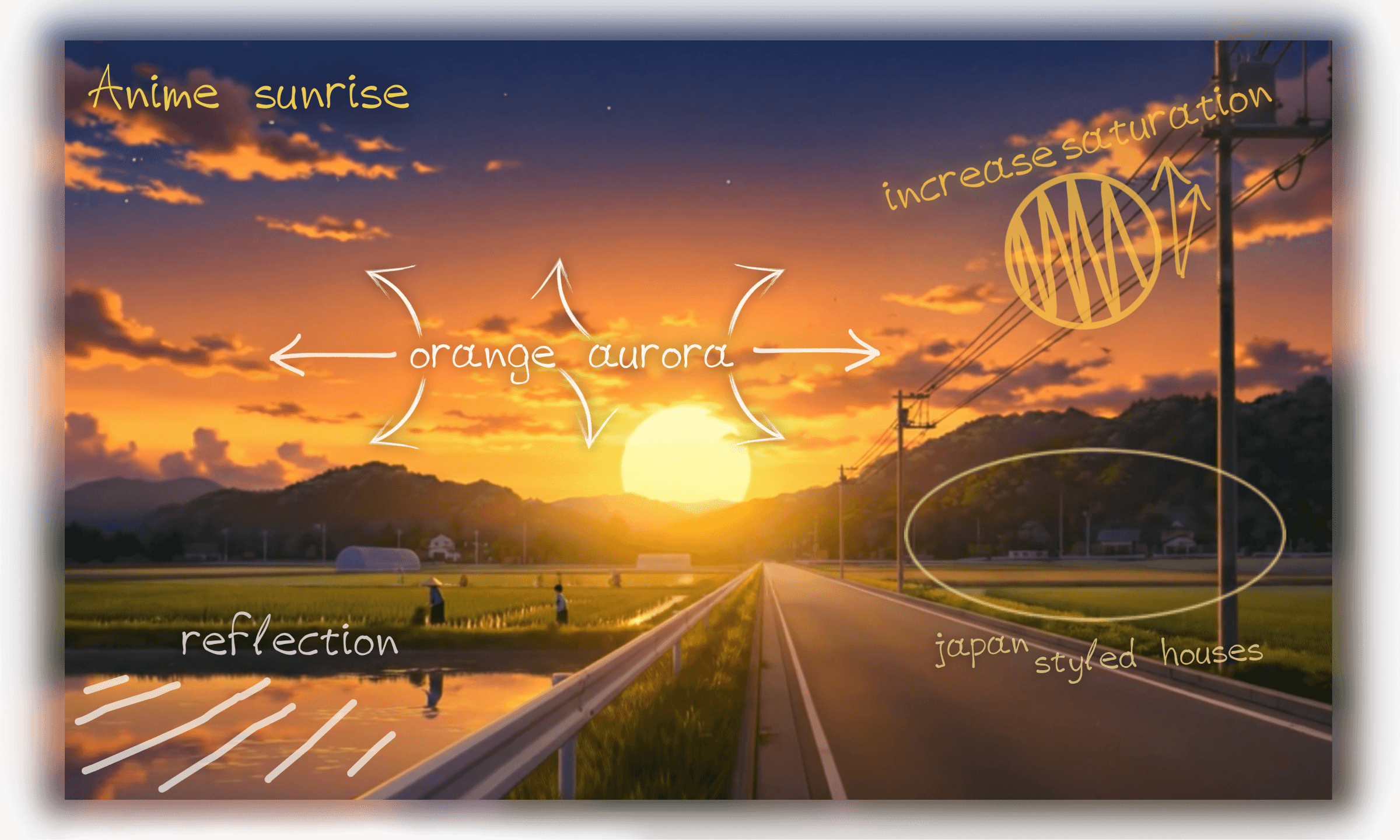

enhancing raw sketchesthis feature uses nanobanana via vertex ai platform to make sketches better.

i'm terrible at drawing so i instantly upgrade my drawing with one click.

generating the animationthis button sends the whole frame, with all the children shapes added through image upload and tldraw tools, as well as a text prompt, to veo 3.

frontend/src/components/canvas/FrameActionMenu.tsx// Capture frame as image

const { blob } = await editor.toImage([shapeId], {

format: "png",

scale: 1,

background: true,

padding: 0,

});

// Send to Veo 3 API

const formData = new FormData();

formData.append("custom_prompt", promptText);

formData.append("global_context", JSON.stringify(context?.sceneState ?? {}));

formData.append("files", blob);

const response = await apiFetch(`${backend_url}/api/jobs/video`, {

method: "POST",

body: formData,

});

const { job_id } = await response.json();

the post request creates a job in the backend to generate the animation.

later in the process, we make a new frame using the final shot of the video and an arrow component that connects them. this behavior occurs infinitly, which is the fundamental concept of flowboard.

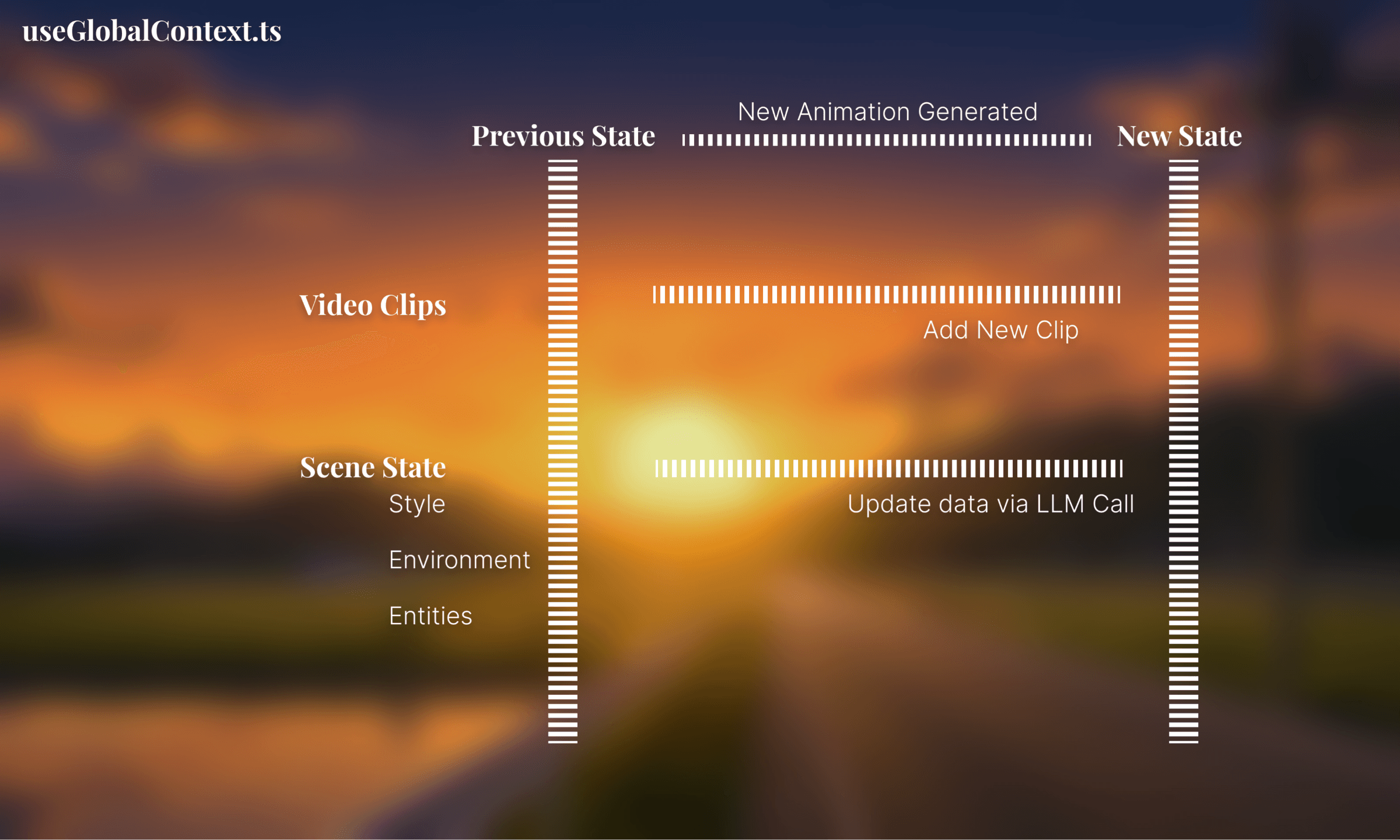

global contextfor animations to be coherent together, we used the idb-keyval npm package for global context.

we manage context though a custom hook: frontend/src/hooks/useGlobalContext.ts, which persists clips and scene context in react state, which gets passed into successive animation calls.

after each animation call, we update this state to reflect the latest animation state.

hackathon mvpour mvp after 36 hours was quite refined. we had all of our core features functional, which meant that it genuinely worked with zero hardcoding or fugazi gimmicks.

although there were a couple of missing features, such as auth, and a couple of odd bugs, which we set to fix after the hackathon. more on this after i introduce the backend.

big props to daniel for carrying the backend.

the backend follows a service-based architecture:

backend/controllers/ http route handlers

backend/models/ dataclasses

backend/scripts/ sql db scripts

backend/services/ logic layer

backend/utils/ helper utils

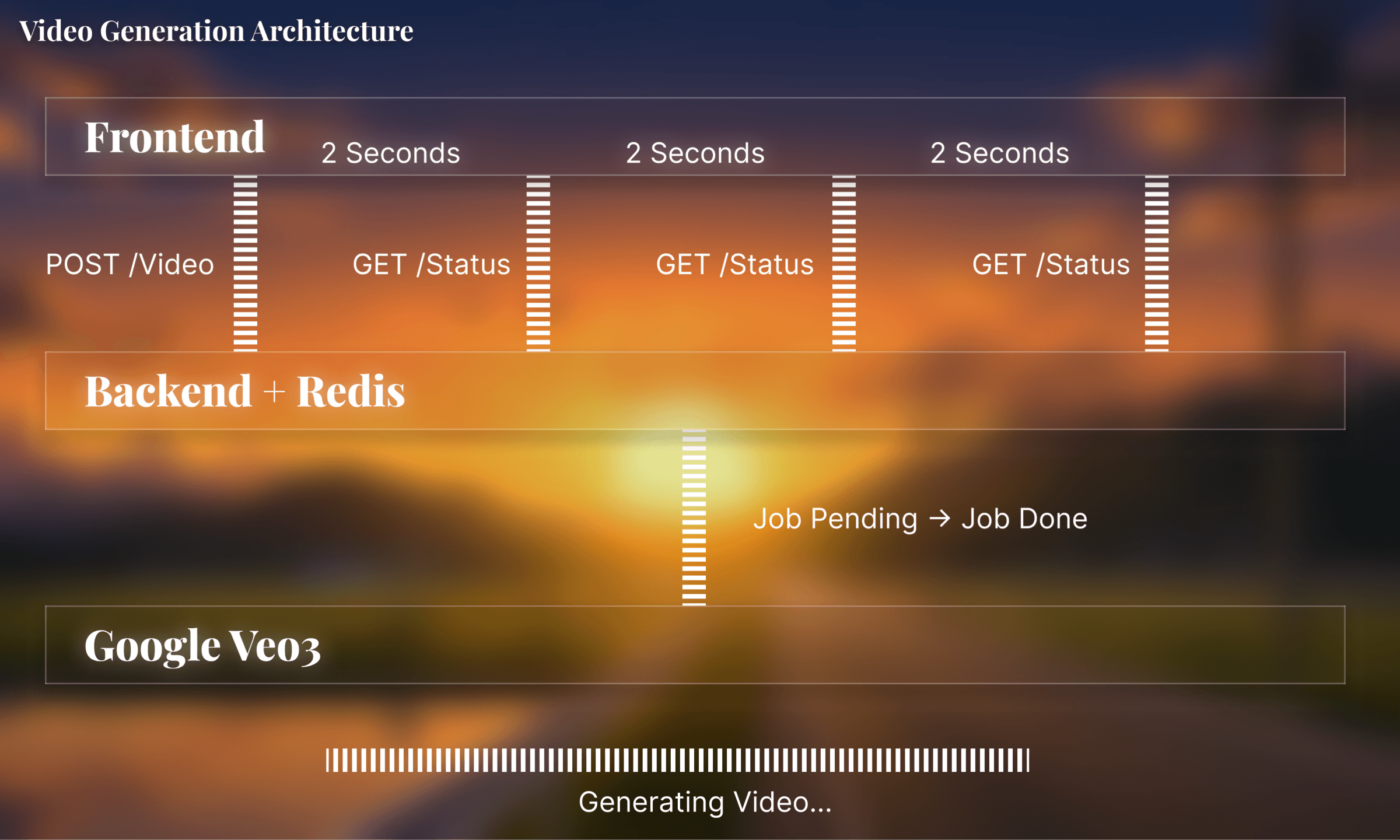

video generationvideo generation follows an async, non-blocking architecture where users get instant job ids and poll for completion.

when a user clicks generate, the frontend captures the frame as a png and sends it with the prompt to the backend:

backend/controllers/jobs.py@post("/video")

async def add_video_job(self, request: Request):

files = await request.files()

image_file = files[0]

# Create job, instant return

job_id = await self.job_service.create_video_job(data)

return json({"job_id": job_id})

the job service creates a unique job id and fires a background task without blocking the response.

in the background task, we parallelize image processing using asyncio.gather() to analyze annotations and remove text simultaneously:

backend/services/job_service.pyasync def _process_video_job(self, job_id: str, request: VideoJobRequest):

# PARALLEL: Analyze annotations + Remove text

tasks = [

self.vertex_service.analyze_image_content(

prompt="Describe animation annotations...",

image_data=request.starting_image

),

self.vertex_service.generate_image_content(

prompt="Remove all text, captions, annotations...",

image=request.starting_image

)

]

# Wait for both to complete

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

annotation_description = results[0]

starting_frame = results[1] # Cleaned image

# Generate video with Veo 3 ...

the vertex service calls the veo 3.1 model and saves videos directly to google cloud storage buckets:

meanwhile, the frontend polls for status by repeatedly calling the status endpoint:

backend/controllers/jobs.py@get("/video/{job_id}")

async def get_video_job_status(self, job_id: str):

jobStatus = await self.job_service.get_video_job_status(job_id)

if jobStatus.status == "waiting":

return json({"status": "waiting", ...}, status=202)

if jobStatus.status == "done":

return json({

"status": "done",

"video_url": jobStatus.video_url,

...

})

upon success, the status check queries google's operation and converts the storage url that was uploaded by the job to a public https link.

now with a public video link, we could display it on the frontend.

this architecture optimizes short video generation: parallel processing and redis caching keep the system efficient.

redis cloudredis acts as a temporary job queue for tracking video generation progress. since veo 3 takes 20-40 seconds to generate videos, we needed fast, ephemeral storage for job state.

redis stores three types of job states with 5-minute ttls for automatic cleanup:

backend/services/job_service.py# Pending: User just submitted, processing hasn't started

self.redis_client.setex(f"job:{job_id}:pending", 300, self._serialize(pending_job))

# Active: Processing with Google, stores operation name for polling

self.redis_client.setex(f"job:{job_id}", 300, self._serialize(job))

# Error: Failed during generation

self.redis_client.setex(f"job:{job_id}:error", 300, self._serialize(error_job))

job data is compressed with lzma before storing to save memory, especially important for operation metadata:

backend/services/job_service.pydef _serialize(self, data: dict) -> bytes:

"""Serialize + compress data for Redis storage"""

return lzma.compress(pickle.dumps(data))

def _deserialize(self, data: bytes) -> Optional[dict]:

"""Decompress bytes from Redis storage"""

if not data:

return None

return pickle.loads(lzma.decompress(data))

when status is polled, redis provides sub-millisecond lookups. once the video is done, the job is automatically deleted from redis:

backend/services/job_service.pyif result.status == "done":

self.redis_client.delete(f"job:{job_id}") # Clean from redis

redis was chosen over a traditional database because job data is temporary, needs sub-millisecond reads for frequent polling, and auto-expires without manual cleanup. it also integrates well with supabase.

hosting the backendi'm leaving it at that, but there are many other aspects of the backend that are worth checking out.

we dockerized the backend and hosted it on google cloud run. we chose to stick with the google platform because the rest of our stack lives on gcp + the generous free trial 🤫

we spent the next week refining the project with the idea of shipping it.

we added auth, integrated a stripe based payment system with autumn, and created a video merging feature that allows users to download storyboards from start to finish.

the ui, concept, and branding were also refined.

goated team

goated teaminstead of studying for our algebra quiz, we launched a week after hackwestern. austin's linkedin post did well: ~100k impressions and 1.5k+ likes. our github repo also took off, this is my first project with more than 100 stars!

for a different perspective, read austin's case study.

here are some cool animations i made with flowboard:

"random entity destroying everything""no entities spawn""arctic winds in san francisco""washington ww2 in art style""grizzly bear enjoying aurora borealis"consider giving it a try!